If you can’t convince them, confuse them.

Harry S Truman

Like free will, health eludes easy definition.

Worse, our understanding of what constitutes “good health” is often shaped by effective marketing and charlatan influencers. We internalize such dietary bogeymen as soy, wheat, and seed oils. We come to believe that green juices, cold plunges, CGMs, and the carnivore diet will provide deliverance.

After a few months of committed practice and subscription fees, many likely return to the familiar comfort of previous behavioral patterns.

I suspect most people in a hurry are left wanting more—a conception of health that is at once simple, sustainable, and firmly based in scientific evidence.

Lest I verge on hypocrisy, this piece will neither advertise products and services nor profess to contain any panaceas.

TL;DR

To improve health, we can focus on:

Reducing visceral fat

Increasing VO2 max

Eating enough protein and fiber every day

Modern medicine gives us several health markers worth tracking, including blood pressure, bone density, and levels of blood sugar, cholesterol, and vitamins. Contending with fewer, more accessible metrics, however, may lead the adoption and maintenance of specific behaviors to be more feasible.

The measures we do follow ideally achieve a certain sweet spot:

They accurately capture our future risk of suffering and death;

They closely correlate with that risk as numbers move up or down.

BMI and body weight have conventionally served in this capacity. Someone whose BMI is too high or low is often judged to be “unhealthy” and advised to change their weight independent of other important markers of health.

As I previously argued, it is time that BMI and weight are dishonorably discharged from their service to public health. They are overly simplistic and lack sufficient distinction to inform risk across diverse populations.

In their stead, we can shift focus towards visceral fat and VO2 max as more precise measures of overall function and well-being. In isolation, these two metrics are among the most meaningful components in the subjective experience of suffering and the objective reality of dying prematurely.

Together, we will call this approach the Double-V Strategy.

By centering our efforts on explicitly reducing visceral fat (instead of broadly “losing weight”) and increasing VO2 max (rather than broadly becoming “more fit”), we can likely achieve more significant improvements in quality of life and more conventional measures of health, such as blood pressure and blood sugar levels.

Additionally, we can concentrate on intake of protein and fiber as a simple means to optimize diet rather than expressly avoiding or restricting dietary items or practices.

Beyond contributing to lower visceral fat levels, prioritizing protein and fiber consumption has the potential for additive benefit to quality of life, overall function, and disease prevention.

We will term this approach the Beans-and-Greens Strategy, rather than the Meat-and-Wheat Strategy. There is nothing wrong with wheat (unless you have a gluten intolerance or insensitivity), but I will argue below that our sources of protein should be primarily, if not exclusively, plant-based.

Vs for Victory

Visceral Fat

I detail visceral fat more substantively in previous posts, including:

The following section adapts material from the above pieces.

Visceral adipose tissue includes the fat deposits around the stomach, intestines, and liver that, unlike subcutaneous fat, cannot be seen at surface level.

While BMI is conventionally used to stratify risk for various chronic diseases and all-cause mortality, visceral fat burden may be more accurate than BMI in predicting risk of heart disease, heart attacks, high cholesterol levels, colorectal cancer survival, prostate cancer, progression of kidney disease, diabetes, and fatty liver disease, as well as all-cause mortality in certain groups.

Visceral fat can be measured through imaging studies, such as MRI, CT, and DEXA scans. Alternatively, visceral fat can approximated by several low-cost tools:

Waist circumference (WC) [video]: while standing up, wrap a flexible tape measure around your abdomen, just above your hip bones and just above your belly button. Measure your waist only after you breathe out; do not “suck” your gut in. Record the value.

Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) [video]: following measurement of your waist circumference, while standing up, wrap a flexible tape measure around the widest part of your hips and butt. Record the value.

Divide your waist circumference by your hip circumference.

Reduction of visceral fat can be achieve through two main strategies— weight loss and physical activity.

Weight Loss

Loss of body mass inherently requires an energy deficit through reducing caloric intake, increasing overall energy expenditure (e.g., more physical activity), or a combination of both.

Established guidelines suggest a deficit of 500 to 1000 calories per day below habitual caloric intake contributes to sustainable weight loss, about two to three pounds (0.9-1.4 kg) per week. Alternatively, daily caloric intake could be reduced to 70-80% of habitual levels.

Over a four- to six-month period, weight loss of 5 to 10% may correspond to a reduction in visceral fat burden by 15 to 20%. Another meta-analysis found that losing about 18 lbs. (8.2 kg) of fat mass could reduce overall visceral adipose tissue by as much as 31%.

Given that weight loss might be neither realistic nor sustainable for all-comers, the most practical approach to reducing visceral fat is likely increasing physical activity.

Physical Activity

I often refer to moderate-intensity, aerobic cardiovascular exercise as “Zone 2” and high-intensity, anaerobic cardiovascular exercise as “Zone 5.”

“Resistance training” is broadly regarded as lifting weights.

In the absence of an energy deficit, resistance training alone can significantly lower visceral fat levels. Some data suggest that Zone 2 training might be more efficacious than resistance training in driving these reductions. These findings often occur without observed weight loss.

Additional studies (1, 2, 3) suggest that Zone 5 sessions have similar efficacy to Zone 2 training in decreasing visceral fat with the added benefit of driving more significant improvements in VO2 max, cholesterol levels, and fasting blood sugar. The time investment for Zone 5 training also tends to be lower than Zone 2 sessions.

Following consensus guidelines (performing 150 to 300 minutes of Zone 2 training or 75 to 150 minutes of Zone 5 training in a typical week) over four to six months may reduce visceral fat by 15 to 20%.

VO2 Max

I detail VO2 max substantively in a previous post from which I adapt the following material.

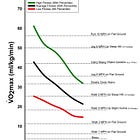

VO2 max refers to the maximum rate (V) of oxygen (O2) one can extract from inhaled air (using the lungs and blood), transport to exercising muscle (using the heart and blood), and utilize through cellular metabolism (using skeletal muscle, namely mitochondria).

The unit of measurement for VO2 max is somewhat clunky: ml/kg/min, the milliliters (ml) of oxygen per kilogram (kg) of body mass utilized in one minute (min).

VO2 max captures the concept of "functional capacity,” the ability to perform tasks and activities essential to daily life with relative ease and efficiency.

Sitting quietly requires a VO2 max of about 3.5 ml/kg/min

Walking at a pace of three miles (5km) per hour, about 12 ml/kg/min

Ascending a single fight of stairs, about 16 to 17.5 ml/kg/min

Walking with groceries (15 lbs, or 6.8 kg), about 17.5 ml/kg/min

Mowing a lawn, about 19 ml/kg/min

Running at a pace of five miles (8.3 km) per hour, about 29 ml/kg/min

Living independently in the eighth decade of life may require a VO2 max around 18 ml/kg/min and 15 ml/kg/min for males and females, respectively.

A vast body of research supports the following assertions:

VO2 max is a useful stand-alone aggregate value for all-cause mortality risk

VO2 max modifies all-cause mortality risk independently of other risk factors

A wide range of individuals— if not virtually all individuals— can meaningfully change their VO2 max

Changes to VO2 max meaningfully modify risk for all-cause mortality and affect important health metrics

Measuring VO2 max

The most accurate measurement of VO2 max takes place in a laboratory setting. A test subject undergoes progressively strenuous exercise on a treadmill or stationary bicycle while their oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production, and ventilation are closely monitored. Ideally, the subject exercises until they are exhausted, termed “maximal exercise.”

VO2 max can also be measured through lower-cost "submaximal exercise" methods:

maximum distance run in twelve minutes (Cooper test);

time to complete a one-mile walk and heart rate at completion;

time to complete a 1.5-mile run or walk;

maximum heart rate (an estimate based on age) and resting heart rate

Free VO2 max calculators can be found at mdapp.co.

On average, data from submaximal exercise testing may differ from an individual’s true VO2 max (as measured through maximal exercise testing) by about 3.5 ml/kg/min on average.

Improving VO2 Max

Both Zone 2 and Zone 5 exercise are capable of improving VO2 max, though Zone 5 is likely more effective. As many as 40% of individuals performing structured Zone 2 exercise may not experience improvements in VO2 max.

Vigorous exercise usually takes the form of high-intensity interval training, or HIIT. In this form of exercise, one performs an exercise at a high intensity for a specific amount of time before resting for the same or a lower amount of time. This work-rest interval is then repeated.

For instance, one might sprint for 20 seconds and then rest for 10 seconds for eight intervals, taking a total of four minutes. (This structure of HIIT is commonly referred to as a Tabata.)

Meta-analyses of clinical trials investigating HIIT find that more significant gains in VO2 max are made compared to Zone 2-based exercise over 4 to 12 months when the following parameters are met:

The overall session lasts at least 15 minutes

For instance, one could perform 2 five-minute high-intensity intervals with a single five-minute rest period in between each interval for an overall session time of 15 minutes.

Running, cycling, and rowing will likely lend themselves best to high-intensity training. Walking might be feasible but will likely require a steep hill, using a treadmill at a steep incline, or carrying weight in a backpack to reach the intended level of intensity.

Within the literature, the Norwegian 4x4 protocol is among the most researched HIIT structures.

When performed three times a week, the Norwegian 4x4 protocol led to a 7.2% increase in VO2 max over eight weeks in healthy males and 4.2% in healthy females. Among both male and female participants, performing the 4x4 protocol three times a week contributed to a 10% increase in VO2 max over six weeks and between a 12% to 15.1% increase over eight weeks.

When modified for walking instead of running, 4x4 intervals were also shown to boost VO2 max by 17.9% over ten weeks in male and female subjects with stable coronary artery disease.

Beans and Greens

Protein

In another piece, I detail my argument for updating the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for dietary protein.

Recent insights from the scientific literature suggest the RDA for protein in healthy sedentary adults and healthy sedentary older men should likely be around 0.9 to 1.2g/kg of body weight. Healthy sedentary older women may require protein intake closer to 1 to 1.3 g/kg of body weight.

Healthy active adults, meanwhile, may benefit from protein intake of 1.6 to 2.2g/kg of body weight (0.73 to 1g/lb. of body weight) per day.

Optimizing protein consumption among older adults can aid in preventing loss of muscle mass, muscular strength, bone density, and immune function, all of which are major contributors to frailty and loss of autonomy. Although there is no silver bullet to halt the effects of aging, consuming enough protein is a step in the right direction.

The protein portion of the Beans-and-Greens Strategy is represented by a legume to connote the importance of plant-based sources of protein. Compared to consuming animals, there are several key advantages in sourcing protein from plants:

Fewer natural resources are required to harvest plants compared to the production of meat, dairy, and eggs

A vast literature suggests there is lower risk of virtually all major chronic diseases among those who consume a plant-based diet. This observation is likely due to lower levels of cholesterol, blood sugar, inflammatory markers, and visceral fat as well as lower blood pressure in this population, although the healthy user bias may dampen the strength of this association.

Conversely, higher consumption of animal-based proteins is associated with increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality as well as increased risk of diabetes and kidney disease

For some, there are ethical concerns inherent to raising and slaughtering billions of animals—independent of their quality of life or the mechanism by which they are killed—that are obviated by only eating plants

Some evidence suggests there is no difference in strength or aerobic exercise performance between individuals who mainly consume animal- or plant-based proteins, although other studies find animal-based protein may be more effective at increasing lean mass than plant-based sources in young adults.

The clear benefits to personal health and environmental sustainability in tandem with ethical considerations should give priority to plant-based proteins in working to optimize diet.

Fiber

I have also written extensively about fiber in a previous post.

The average American currently consumes about 16 grams of fiber per day, and just five per cent of the population meet the FDA recommendation of 28 grams of fiber per day.

A series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of 185 prospective cohort studies and 58 clinical trials concluded that consumption of 35 to 40 grams of fiber per day confers greater protection from cardiovascular disease, type two diabetes, and colorectal and breast cancer compared to 25 to 29 grams.

There is also evidence that optimal fiber intake can lower cholesterol and blood pressure (reducing risk of heart disease and stroke), regulate blood sugar and insulin levels (reducing risk of diabetes), promote weight loss, and relieve constipation.

Increasing Fiber Consumption

First, perform a “fiber audit” to assess how your current consumption differs from the above guidelines. Depending on the difference, you may consider adding high-fiber foods like raspberries, green peas, and black beans as a snack or side helping with a larger meal.

Alternatively, taking a supplement like psyllium husk (the main ingredient in Metamucil) is a cost-effective way to obtain extra fiber. One serving contains about 6-7 grams of fiber and costs about $0.20. You may consider fiber gummies, which provide about 6 grams of fiber for $0.30 per serving.

To reach 28 grams from an average intake of 16 grams of fiber, one would benefit from consuming either two servings of high-fiber foods or combining one high-fiber food with a serving of supplemental fiber.

A focus on simple, science-backed approaches can provide a clearer signal amidst the noise within the health and wellness space.

By prioritizing visceral fat reduction, improving VO2 max, and incorporating enough dietary protein and fiber, we can build a sustainable path to better health.

Very informative and encouraging along with the ‘how-to’ to achieve these objectives

Additionally it was easy to read lending itself to be shared with others who could benefit from this approach to healthier living

Thank you