If pressed, no one can tell you exactly what defines a “superfood.” They just broadly have a lot of “nutrients.” The shared characteristic of avocados, walnuts, kimchi, dark chocolate, açaí berries, goji berries, chia seeds, kale, and quinoa is probably just their “super” price.

The nutrient actually worth obsessing about is quite boring and overlooked: fiber. Virtually no other nutrient can claim the same amount of health benefits as this humble carbohydrate.

Adequate fiber consumption can lower cholesterol and blood pressure (reducing risk of heart disease and stroke), regulate blood sugar and insulin levels (helpful in managing diabetes), promote weight loss, and relieve constipation.

Fiber intake is also associated with reducing the risk of diverticulosis, dementia, fatty liver disease, colorectal cancer (and its survivorship), ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, liver cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, oropharyngeal and esophageal cancer, prostate cancer, and endometrial cancer. (Some of these relationships are notably confounded by the healthy user effect: individuals consuming high amounts of fiber likely have other healthy practices that also account for these observations.)

The bulk of the evidence regarding fiber is nonetheless clear. If we intend to live a long, enjoyable life, we must strive to obtain enough fiber in our diets.

Obtaining sufficient fiber is easier said than done. The average American consumes 16 grams of fiber daily and only five per cent of the population meet the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommendation of 28 grams. The optimal amount of daily fiber intake, meanwhile, is likely even higher at 35 to 40 grams.

We clearly have some work to do.

This piece will first review the major attributes of fiber before discussing other pertinent topics and best practices to increase fiber intake.

Soluble and Insoluble Fiber

Fiber is a non-digestible form of carbohydrate classified as either soluble or insoluble.

Soluble fiber dissolves in water and is fermented by bacteria in the large intestine into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). SCFAs stimulate the growth of beneficial bacteria in the microbiome, termed a “prebiotic” effect. Prebiotics are now found in capsules, gummies, and even soda, although they can easily be obtained through dietary fiber.

SCFAs reduce the amount of cholesterol carried by low-density lipoproteins, called LDL-C (the fuel source for atherosclerotic plaques) through two mechanisms:

The growth of beneficial bacteria decrease absorption of dietary cholesterol and saturated fat as well as natural cholesterol released from the liver. These molecules are then fecally eliminated.

SCFAs also mimic statins, the major drug class used to lower LDL-C, by causing the liver to produce less natural cholesterol. Supplementing with soluble fiber may in fact double the cholesterol-lowering effect of statins.

This prebiotic effect also slows digestion of carbohydrates, preventing spikes in blood sugar that contribute to elevated insulin levels and promote insulin resistance, the bedrock of type two diabetes.

Separately, there is evidence that SCFAs reduce inflammation, improve immune function, and inhibit tumor cell proliferation, potentially explaining the above observations regarding cancer and fiber intake.

Soluble fiber is commonly found in oats, nuts, seeds, beans, lentils, peas, and fruits. It is also found in psyllium husk, the main ingredient in the fiber supplement Metamucil.

Insoluble fiber cannot dissolve in water, thereby adding bulk to stool and alleviating constipation. Insoluble fiber also promotes the perception of “fullness” after eating by delaying transit of food and releasing satiety hormones, which together tend to stimulate weight loss.

Insoluble fiber is found in wheat, whole grains, vegetables, and the skins of most fruits.

While important differences exist between soluble and insoluble fiber, their relative amounts are not specified on most food labels. Most epidemiologic nutrition research also does not parse soluble and insoluble fiber when collecting data on dietary consumption.

Given its myriad benefits, having more soluble fiber than insoluble fiber is probably more advantageous but simply obtaining an adequate amount of fiber on a daily basis should be the foremost goal.

The Benefits of a High-Fiber Diet

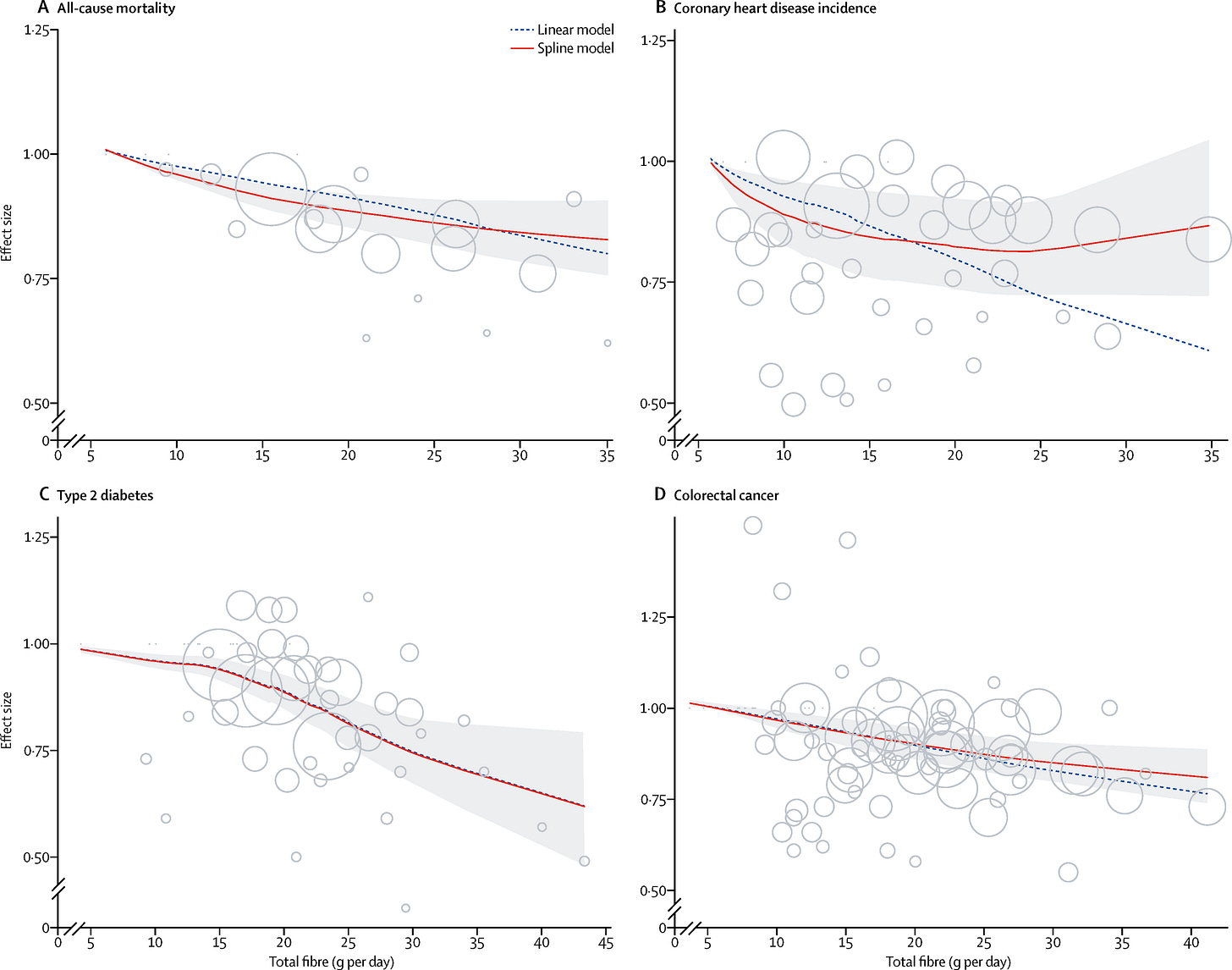

The recommendation to consume 35 to 40 grams of fiber per day stems from work showing a clear dose-response relationship between fiber intake and all-cause mortality, coronary heart disease, type two diabetes, and colorectal cancer.

In other words, one gains progressively more health benefits as they increase their fiber intake.

This dose-response benefit is notably less pronounced in coronary heart disease incidence as seen in quadrant B, likely due to a dearth of studies examining diets with greater than 25 grams of daily fiber. Other work does find a more robust inverse dose-response relationship between CHD incidence and fiber intake. As a result, I do not expect there to be an increased incidence of CHD as fiber intake escalates.

High Protein, High Fiber: Competing Interests?

In addition to increasing fiber intake, I also advocate for consuming a high amount of protein.

Within the literature, there is evidence that fiber decreases the apparent digestibility of protein by up to 10 per cent as measured by nitrogen excretion. It is unclear whether these findings translate into decrease absorption, and thus usability, of protein.

When increasing dietary fiber, it is likely not necessary to increase protein intake in tandem to compensate for decreased digestibility. More research is needed to make a firm recommendation to this effect.

Nonetheless, given this theoretic relationship with protein one might err towards a fiber intake closer to 40 grams daily rather than blithely consuming as much as possible. Only a few studies (1, 2) assess the associations of an ultra-high fiber diet (>45 grams per day) on biomarkers and disease outcomes. As such, it is also unknown if there is any clear benefit to very high fiber intake.

The Role of Low-Fiber Diets

Although fiber has myriad health benefits, restricting fiber intake to about 10 grams or fewer per day may have therapeutic value for some gastrointestinal disorders including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).

Such approaches, like the low-FODMAP diet, are often initiated with the guidance of a healthcare professional.

How to Increase Fiber Intake

Although consuming 35 to 40 grams of fiber per day is likely to be more beneficial than 28 grams, aiming for the latter goal is an excellent starting place to implement changes.

The first step is understanding how much fiber is already obtained in a typical day. This audit can be performed by keeping track of food labels found on most food products. A website or smartphone app with nutritional information can also help make this calculation.

This baseline intake will dictate whether your fiber goal can be reached by making dietary changes alone or with additional supplementation. The Mayo Clinic lists several high-fiber foods like raspberries, green peas, and black beans that can be easily integrated as a snack or side helping with a larger meal.

For those unable to access these items, psyllium husk (the main ingredient in Metamucil) is a cost-effective way to obtain extra fiber. One serving contains about 6-7 grams of fiber and costs about $0.20. Alternatively, you may consider fiber gummies, which provide about 6 grams of fiber for $0.30 per serving.

To reach 28 grams from an average intake of 16 grams of fiber, one would benefit from consuming either two servings of high-fiber foods or combining one high-fiber food with a serving of supplemental fiber.

By way of suggestion, I start my day with a bowl of “loaded oatmeal” that alone contains about 25 grams of fiber. The recipe can be found below. I usually have a can of chickpeas (20 grams of fiber) for lunch and a can of black beans (30 grams of fiber) for dinner every few nights.

Although these suggestions might not be palatable for everyone, they help to illustrate that with a few relatively simple changes, intake of fiber can be optimized and considerable health benefits reaped.

Loaded Oatmeal

½ cup old-fashioned oats (microwaved with water or beverage of your choice)

¼ cup blueberries

1 banana

2-3 tbsp. granola

2-3 tbsp. peanut butter

2 tbsp. walnuts

1 tbsp. chia seed

1 tbsp. flax seed

Like previous articles, very informative which is aided/elevated by being very readable. Understandable with any uncommon words quickly explained within the sentence. Bonus with examples of how to begin to achieve the benefits of the topic-Fiber. The tie into previous article regarding protein was nicely done as well. Good encouraging reading ;)