The limits of my language mean the limits of my world

Ludwig Wittgenstein

I recently came across a somewhat obscure word in North Woods, a delightful novel by physician-writer Daniel Mason:

Uxorious, meaning to have or show an excessive or submissive fondness for one's wife, stemming from the Latin uxor for wife.

I revealed this discovery to a few friends during a lull in conversation over drinks.

“So, essentially a simp?” I was asked. “Or being p****y-whipped?” Modern-day parlance apparently knows few limits.

A bit deflated, I then remarked on the lack of a compelling term for the inverse scenario. What would we call a wife who has an excessive or submissive fondness for her husband? I had no idea. Neither did my interlocutors, who wished desperately for the subject to change.

Surely there is no absence of words containing intense specificity within language. German is perhaps most famous for this—Torschlusspanik, for instance, is the fear of being left behind or time running out, directly translated as “gate-shut-panic.”

Just as striking, however, is when language fails to capture common phenomena within a society.

Indeed, Anglophone culture has almost certainly long contained a tacit expectation of a submissive fondness of a wife towards her husband. For women entering marriages, comporting to such behavior might well go without saying, as they emulate members of their family or community over generations.

Uxorious, then, likely only gained traction as a useful term because such behavior would be deemed abnormal and divorced from the conduct expected of a husband towards his wife. Even now, the most ingenious Gen Z or Gen Alpha wordsmith might struggle to coin a word that describes the inverse of a “simp” or someone who is “p***y-whipped.”

While this might be a fun little observation, I hesitate to claim there is any real impact from the presence or absence of certain words within language. The existence of uxorious and the lack of an inverse term likely held little influence on the misogynistic structure of marriage in Anglophone countries throughout history.

Color me a critic of linguistic determinism, which argues that language immutably determines and restricts thought patterns, behavior, and perceptions. Cue Wittgenstein’s epigram. (A more recent modern example is the 2016 film Arrival.)

Due to a lack of concrete evidence, linguistic determinism has largely been discredited by scholars. Linguistic relativity is a more flexible version of its thesis, contending that language does shape experience but does not limit perception.

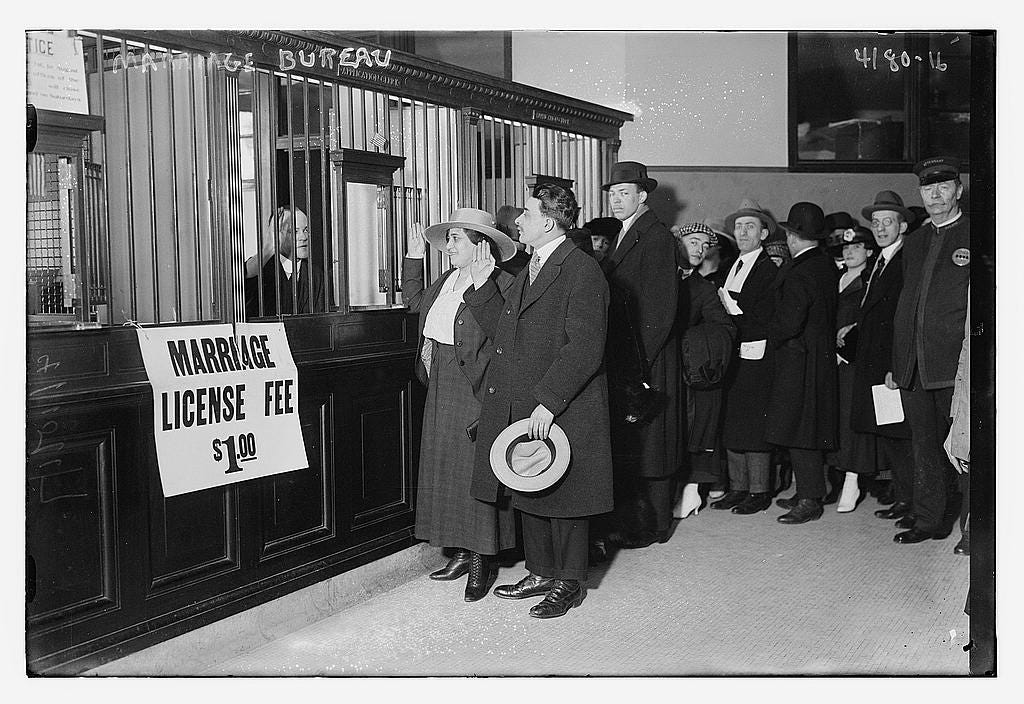

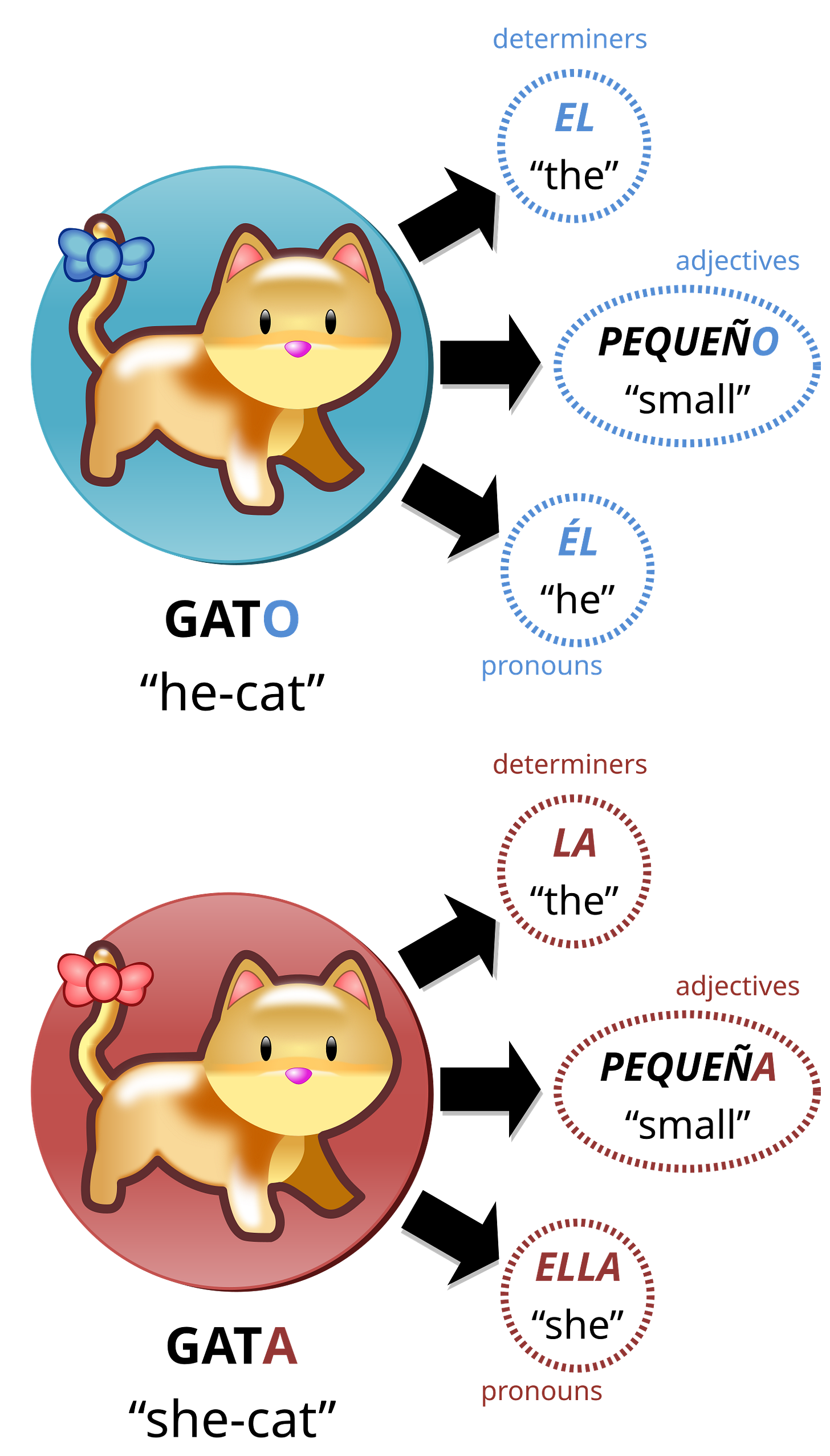

Empiric evidence for linguistic relativity is indeed found among languages that utilize gendered nouns. As many as half of the 7,000 extant languages spoken by humans may contain grammatical gender.

Several languages divide nouns into either a masculine or feminine class, which specifies the agreement of articles, adjectives, and pronouns. Notably, Old English contained grammatical gender, which underwent a steady decline following the Norman Conquest in 1066. By the time Chaucer wrote The Canterbury Tales in the late 14th century, gendered nouns had almost entirely vanished.

In Modern English, gender is only found in pronouns, certain roles played by women (e.g., hostess), and the enduring feminine identity of ships.

Some empirical research suggests that native speakers of languages with grammatical genders tend to describe an object with traditionally masculine or feminine adjectives that align with that object’s grammatical gender.

For instance, German for “bridge,” die brucke, is feminine, while the Spanish word, el puente, is masculine.

When observing the same bridge in one classic study, German-speakers more likely used traditionally feminine adjectives like “lovely” or “intricate,” whereas Spanish-speakers described the structure with such masculine words as “heavy” and “jagged.”

Another study examined two variants of Norwegian (Bokmål and Nynorsk) that contain the same masculine nouns but otherwise differ in grammatical gender— feminine nouns in Nynorsk are treated as neutral (known as neuter in linguistics) in Bokmål.

Participants then assigned either a male or female voice to a series of nouns. Whereas both groups preferred a male voice to recite masculine nouns, Bokmål speakers showed no preference between voices for neutral nouns. The Nynorsk group, as anticipated, usually selected a female voice for feminine nouns.

These are interesting findings to share at a dinner party, especially if you do not want to be invited back, but these observations likely carry little real-world impact.

One civil engineer’s survey of bridges in Europe finds, for instance, “there is no discernible structural difference between bridges in France and Germany, at least related to gender issues.” (The word for bridge in French, like Spanish, is masculine.)

On balance, 19th-century linguistic theories likely do not hold the influence their early purveyors imagined. The nuances of language remain nonetheless captivating, serving as testament to the near-endless expansion and expression of human culture throughout our species’ history.

If you haven’t already, you may find interest in the book “Invisible Women” which looks extensively at gendered language.