A brief assortment of miscellaneous facts, which verge on trivia, from my medical training and reading.

Blue Blood

Iron is an indispensable element found in hemoglobin, a component of red blood cells, which transports oxygen and carbon dioxide in our bodies.

When iron levels are low, patients may develop iron-deficiency anemia, the most common type of anemia, leading to fatigue, weakness, and a curious symptom called pica, the consumption of non-nutritive items—most classically ice, itself known as pagophagia.

In fact, a craving for ice tends to be a very strong predictor for iron-deficiency anemia.

Hemoglobin, however, is only found in vertebrates, with the exception of the crocodile icefish. Invertebrates instead use a metalloprotein known as hemocyanin, formed from two copper atoms. While a bond between iron and oxygen results in a red color (hence, red blood cells), when copper bonds with oxygen, a blue hue results.

The blue “blood” of horseshoe crabs, which have existed in their current form for about 250 million years, has been used for the last five decades to test for bacterial contamination in medical devices and pharmaceuticals.

Catamenial Pneumothoraces

The endometrium is the inner lining of the uterus (commonly called the “womb” when a woman is pregnant) that periodically grows throughout the menstrual cycle. If a pregnancy does not occur, the endometrium is shed during menses (i.e., a period).

The condition endometriosis is the presence of endometrial tissue in areas outside of the uterus, including the nearby fallopian tubes and ovaries. During the hormonal fluctuations of menstruation, patients with endometriosis may experience painful periods, painful bowel movements, heavy bleeding, and irregular spotting.

Rarely, endometrial tissue can implant elsewhere in the body.

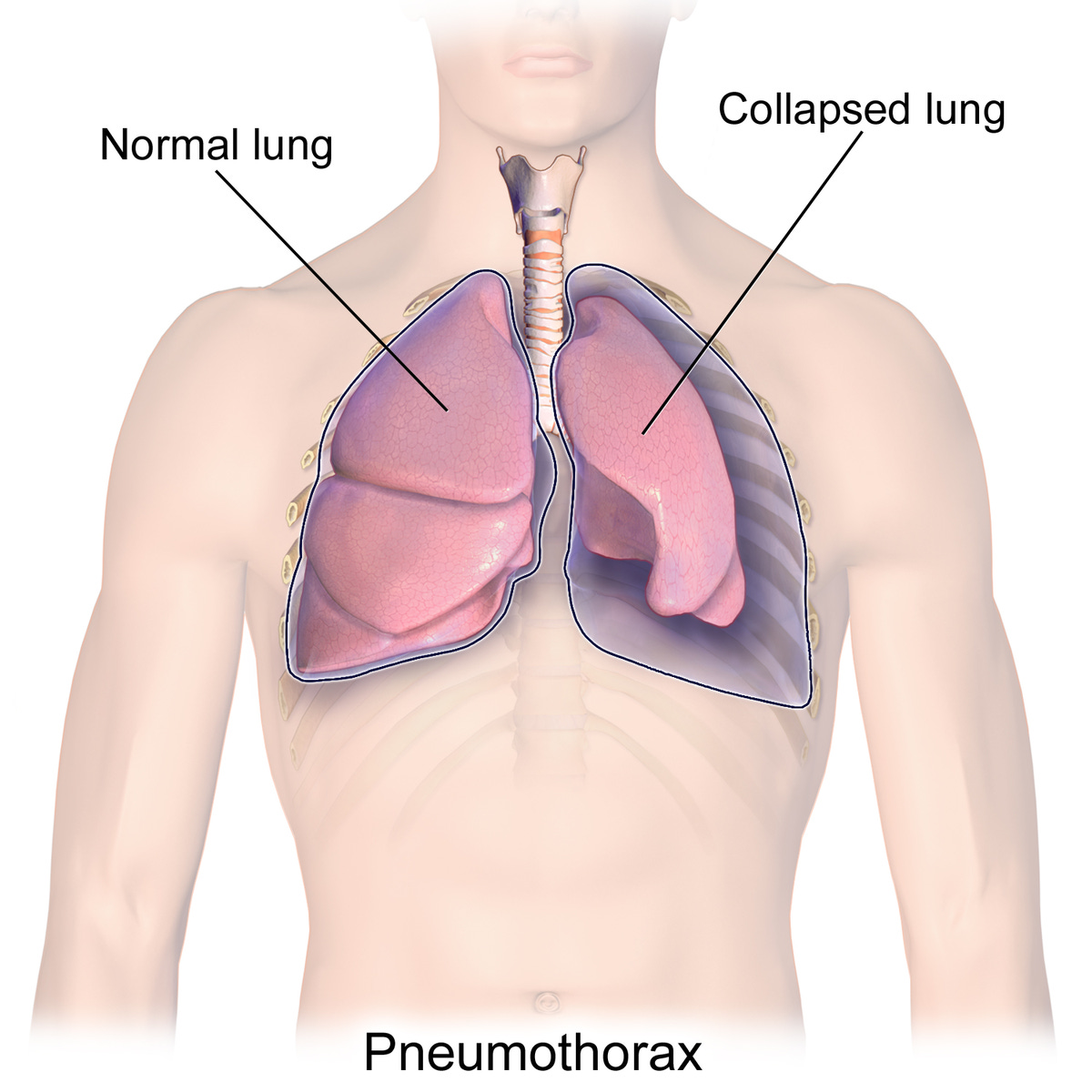

The pleurae are thin membranous surfaces that surround the lungs and help them to expand and contract appropriately. They are known as a “potential space,” a largely empty area that can accommodate fluid or air, sometimes with devastating consequences.

A pneumothorax is the presence of air within the pleural cavity, which can limit the lung’s ability to expand, leading to collapse. Pneumothoraces may occur spontaneously, without any apparent cause, or due to trauma or injury.

A tension pneumothorax occurs when air within the pleural space becomes entrapped and may rapidly expand, drastically reducing oxygen levels as well as blood pressure by pushing on adjacent blood vessels. Although death is fairly rare, tension physiology requires swift recognition and treatment (first responders may emergently place a needle in the front of the chest, allowing the air to escape.)

A catamenial pneumothorax is an especially rare condition in which a spontaneous pneumothorax recurs during or around a menstrual cycle. (“Catamenial” comes from the Greek katamenios, meaning monthly.)

The exact cause of catamenial pneumothoraces is poorly understood but is hypothesized to result from endometriosis within the pleural cavity. Potential treatments include hormonal suppression as well as pleurodesis, a surgical procedure that removes a portion of the pleural space to prevent recurrent pleural effusions or pneumothoraces. As pleurodeses reduce the ability of the lung to expand and contract, these procedures are often pursued after more conservative management fails.

Blood Marrow Transplant and Blood Type Conversion

Bone marrow contains specific stem cells that covert into precursor cells to red blood cells (RBCs) under the influence of a hormone released from the kidneys called erythropoietin, or EPO.

(The illegal use of EPO was rampant in professional cycling at the turn of the 20th century. In addition to other performance-enhancing drugs, Lance Armstrong credited his seven Tour de France victories to the hormone.)

All RBCs display several surface markers called antigens. The presence or absence of two major antigens, A and B, determine blood type in humans. The most prevalent blood type, O, refers to RBCs that do not contain the A or B antigen.

Conventionally, the presence or absence of another group of antigens known collectively as Rh, or rhesus, factor, also characterizes blood type as either “positive” or “negative,” respectively.

Several forms of blood cancer, anemia, and immunodeficiencies can be effectively treated with bone marrow transplants. Similar to matching blood types between patients for a blood transfusion, finding a successful match between a bone marrow donor and recipient depends on another set of antigens present on nearly all cells in the body called HLA, or human leukocyte antigens.

The National Donor Marrow Program (NDMP) maintains a database of HLA types among volunteer donors. When a patient is in need of a bone marrow transplant or other form of cell therapy, their HLA type is compared against the database to determine if a volunteer possesses a suitable match.

Please consider joining the NDMP here.

Although a recipient and prospective donor might have a compatible set of HLAs, they do not necessarily need to have the same blood type. As bone marrow contains stem cells that transform into red blood cells, the recipient’s blood type will gradually convert to the donor’s blood type in the first year after transplant.

There are also several instances of bone marrow transplants coincidentally leading to remission of HIV among patients receiving therapy for cancer. The donated bone marrow was later found to possess rare genetic mutations that increased the ability of immune cells to fight HIV. Recipients were later able to discontinue HIV treatment while maintaining an undetectable viral load, which measures whether the virus can be spread to others.

Menstruation is (almost) unique to humans

Menstruation is defined as the periodic shedding of endometrium, the lining of the uterus where a fertilized egg typically implants during pregnancy.

Homo sapiens are one of few species known to have menstrual cycles. Besides humans, only higher primates (other great apes; Old World Monkeys; New World Monkeys), four species of bat, the elephant shrew, and one species of spiny mouse have been observed to menstruate.

Among these species, only humans and chimpanzees overtly menstruate by shedding the endometrium through vaginal bleeding. All other placental mammalian species are thought to undergo concealed menstruation in which the expanded endometrial lining is reabsorbed rather than more visibly shed.

To be sure, other primates do display certain telltale signs of ovulation—most classically enlargement around their genitals, tantalizingly known in the literature as maximum swelling phase, often abbreviated as MSP. (Cringe.)

There are several theories in evolutionary biology for the development of overt menstruation. Among them is the conflict hypothesis, which posits that the endometrium evolved to become thicker and more vascular to prevent lasting damage from the placenta. As a result, the endometrium is less able to be fully reabsorbed during menstruation, leading excess blood and tissue to be released externally.

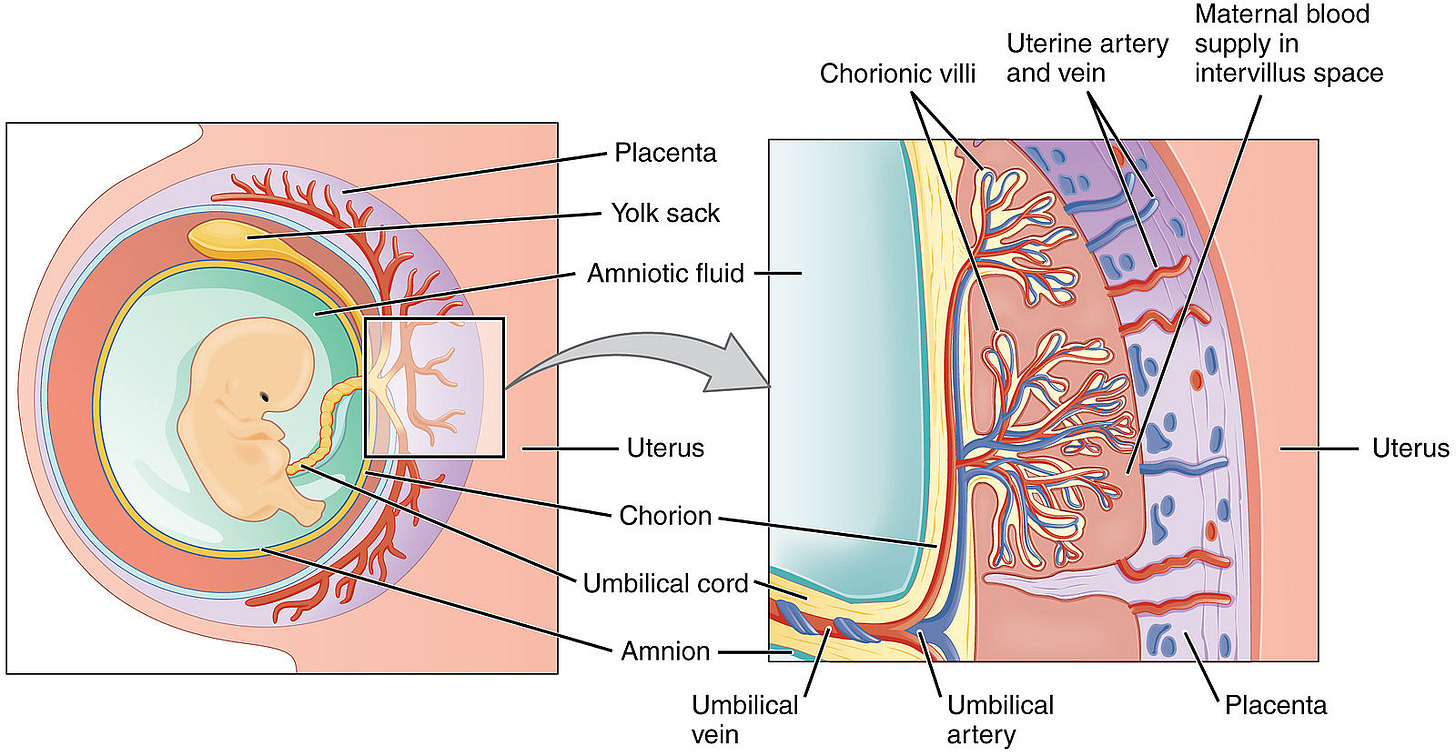

(Recall that the placenta lies along the surface of the uterus and is connected to the fetus through the umbilical cord, helping to shuttle oxygen, nutrition, and waste between mom and her baby.)

Compared to other mammals, human embryos and placentas are particularly invasive, tunneling deep into the uterine lining to gain access to as many of mom’s blood vessels as possible. As part of this process, fetal cells “remodel the endometrial spiral arteries into low-resistance vessels that are unable to constrict,” thereby ensuring uninterrupted blood flow to baby.

This invasiveness and remodeling is a double-edged sword, though.

When the placenta attaches too deeply to the uterus (placenta accreta spectrum), a pregnancy becomes higher-risk, heightening complications like excessive bleeding and infection, sometimes warranting the removal of the uterus (a hysterectomy) during birth.

Placental hormones released into mom’s blood also increase her insulin resistance (to augment the supply of blood sugar to the fetus), which may unintentionally lead to gestational diabetes and cause macrosomia, or excessive fetal growth. Too much of a good thing.

Additionally, dysfunctional remodeling of spiral arteries in the uterus can lead to a condition called preeclampsia, characterized by elevated blood pressure and excessive protein in the urine as well as sometimes swelling of the hands and feet. Preeclampsia can progress into a more severe condition leading to liver and kidney damage as well as seizures, which can be life-threatening for mom and baby.

Given the myriad risks that accompany pregnancy even among healthy women, receiving routine prenatal care from an obstetric healthcare professional is imperative.

The average age of menarche decreasing is not cause for alarm

Menarche marks the first menstrual period experienced in adolescence. Several cultures celebrate this occurrence as a major rite of passage into womanhood.

There is something of a moral panic regarding when modern girls get their first periods. Alarmists, like Christopher Ryan in Civilized to Death, contend that “exposure to estrogenic contamination from plastics, growth hormones in livestock, and added sugar” have dramatically lowered the age of menarche.

This contention finds its provenance in work by Dr. James M. Tanner, who would famously lend his name to the stages of sexual maturity.

Writing in 1962, Tanner declared “the age of menarche has been getting earlier by some four months per decade in Western Europe over the period of 1830-1960.” Whereas a typical girl in 1840s Western Europe was 17 years old when she had her first period, this age had plummeted to 13 years on average in the West by 1960.

This purported trend set off alarm bells in the United States. Magazines like Newsweek and The Nation published exposés on the rising rates of teenage sexuality and pregnancy, laying blame on earlier maturation among girls.

The statistic was excellent fodder for pessimism, giving credence to claims about the evils of plastics and pesticides as well as the whole of secular modernity.

It’s too bad that Tanner’s data only told part of the story.

By the 1980s, population health experts began to take issue with the methods employed by Tanner in making his pronouncements. Dr. Vern Bullough spearheaded the criticism, noting in the journal Science that all of Tanner’s data for the 19th century came from small, isolated samples in Norway, Finland, and Sweden, each rife with outliers.

Only in one dataset from Norway in 1844 was the mean age of menarche actually reported at 17. Larger, more diverse samples from the Netherlands, Great Britain, and the U.S. were only included from the 1940s onwards.

With Bullough’s inclusion of additional data from the 19th century, the drop is far less significant, decreasing from around 14 to 15 years old in 1840 to 12 to 13 years in the late 1970s.

Bullough also included evidence from Western Antiquity and the later Middle Ages, placing the timing of menarche at between the ages of 12 to 14. Another review in 2016 places the age of menarche among Neolithic and Paleolithic populations at between 7 and 13 years of age.

The supposed ills of modernity have not made a girl’s first period arrive earlier. Instead, the veritable ills of the first decades of the Industrial Revolution (poor nutrition, scanty hygiene, chronic illness, and the near-continual exposure to stressors) likely delayed the maturation of girls by several years, accounting for the trends observed by Tanner.

Only with consistent improvement in socioeconomic conditions, cleaner living standards, and advanced medical care did pubertal development return to its previous timing and then notably decrease slightly further.

In the United States, the average age of menarche is currently about 12.25 years old, which has now been stable for the past forty years.

Very fascinating tale of a brief evolutionary journey of blood and its critical role to life. Makes me want to know more