Modern humans are constantly in a hurry. If tasks and responsibilities can be finished more quickly, then by God, let us grind.

No surprise, then, that high-intensity interval training (HIIT) captured the public’s attention. HIIT was billed as an easy solution to the fitness equation. With HIIT, one need only exercise for a short duration of time to reap considerable benefits.

The central conceit is fairly simple: you perform some exercise—say, jumping jacks or running—at the highest possible intensity over a short burst of time, and then briefly rest before repeating the cycle.

Perhaps the most popular protocol comes eponymously from the Japanese scientist Dr. Izumi Tabata. A tabata lasts four minutes during which eight cycles of work are performed: 20 seconds of an exercise, followed by 10 seconds of rest.

Although tabatas formed a large portion of the fitness classes I taught while at university, I have since become an apostate for many forms of HIIT.

“High intensity” is usually equated to “move faster,” leading proper form for a given movement to often be ignored. When performing bodyweight exercises, such as push-ups or sit-ups, poor form is somewhat less likely to lead to injury. But when loading joints with dumbbells or a barbell and then attempting to move that weight as quickly as possible, the threat of injury creeps higher.

Beyond injury, some devotees of high-intensity training might end up lulled into thinking that some nominal amount of exercise, like five or ten minutes per day, is all that is required to optimize health.

Certainly, performing some exercise will always remain preferable to performing no exercise, provided the physical activity is being performed safely. But for one whose goals are rooted in both a higher quality of life and a longer length of life, there are different, and arguably better, approaches.

Sadly, these alternative approaches do involve swallowing a rather bitter pill.

The Long Road to a Long Life

For appreciable benefit to healthspan (a long, healthy life), one should perform about two to four hours of cardiovascular exercise each week. So much for five minutes a day.

The above recommendation is actually nothing new. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.K.’s National Health Service advise that adults obtain 150 to 300 minutes of “moderate” intensity physical activity or 75 to 150 minutes of “vigorous” intensity physical activity in a typical week. A roughly equivalent combination of both, they write, is ideal.

Research by the American Heart Association suggests that obtaining this amount of cardiovascular exercise can lower the risk of developing type 2 diabetes by 25 to 35 per cent and decrease mortality from cardiovascular disease by 40 per cent.

Zoning Out

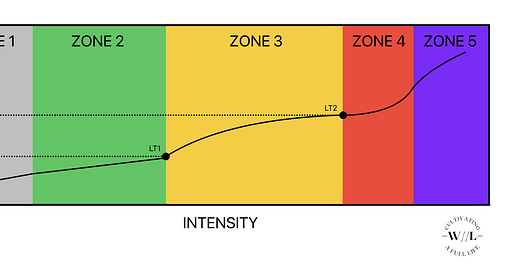

These broad guidelines can be made more precise and actionable by using a framework that divides exercise intensity into five specific zones (i.e., Zone 1, Zone 2, Zone 3, Zone 4, Zone 5).

These zones do not refer to the five heart rate zones found on a wearable device or the seven functional threshold power (FTP) zones used in cycling.

In this framework, each zone instead pertains to a specific range of lactate measured in the blood following a period of exercise.

(As an aside, a simpler paradigm uses just three training intensity zones based on blood lactate levels and is more frequently found in the exercise physiology literature. Peter Attia, a well-known health influencer, needlessly uses a five-zone model popular in cycling, which has in turn become more established among his audience. See more in the Appendix.)

Aerobic Exercise = Zone 2

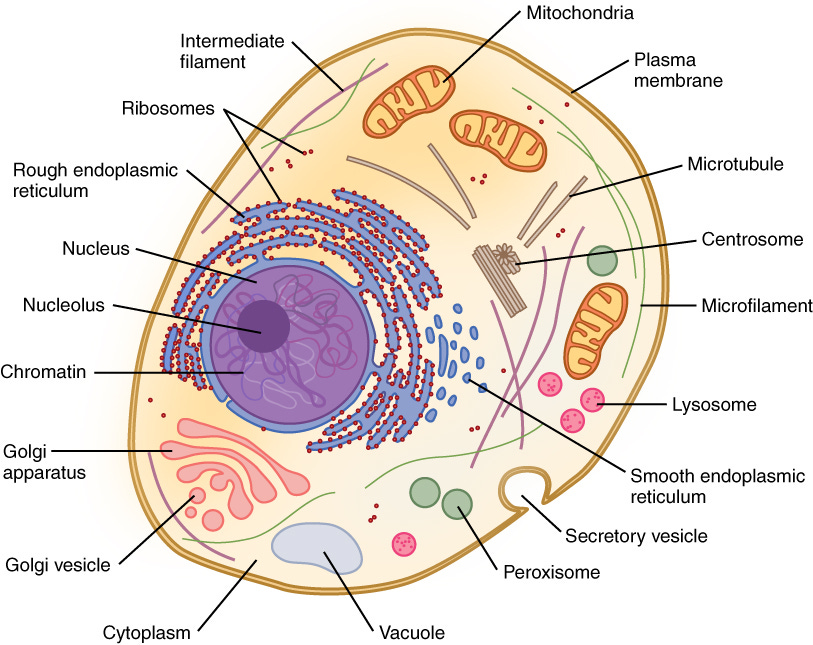

At rest and during low- to moderate-intensity exercise, muscle fibers mainly create energy in the form of ATP through oxygen-dependent (“aerobic”) processes. Aerobic energy generation takes place in mitochondria.

As a result, low- to moderate-intensity exercise is often called aerobic exercise. This piece will refer to aerobic exercise as Zone 2.

Anaerobic Exercise = Zone 5

With higher-intensity exercise, aerobic processes alone are not able to create enough energy to sustain the work of muscle fibers. At this time, a larger proportion of energy is created through oxygen-independent (“anaerobic”) processes within the cytosol of cells, outside of mitochondria.

Vigorous-intensity exercise, or anaerobic exercise, will be referred to as Zone 5.

These anaerobic processes create byproducts such as lactate, which can be measured in blood. (While muscular fatigue after exercise was once believed to stem from the accumulation of lactate, this is increasingly thought to be false.)

The concentration of blood lactate can provide direct insight into the intensity of an exercise session and the degree to which anaerobic metabolism was utilized.

In their purest definitions:

Zone 2: blood lactate ≤ 2 mmol/L

Suggesting that an exercise session was primarily or entirely aerobic.

Zone 5: blood lactate ≥ 4 mmol/L

Suggesting that the session was intense enough to require a higher degree of anaerobic energy production.

Even under fully aerobic conditions, some lactate will still be formed. As such, concentrations of blood lactate are rarely, if ever, found to be zero.

(Blood lactate between 2-3 mmol/L is defined “Zone 3,” whereas lactate between 3-4 mmol/L is “Zone 4.” Again, Attia’s popularization of this five-zone model adds an unnecessary layer of complexity. See Appendix.)

Endurance training sometimes employs the term LT or “lactate threshold,” the point at which lactate production exceeds the ability of mitochondria to process lactate to create ATP. As a result, lactate begins to accumulate.

Historically, LT was thought to uniformly occur when blood lactate first exceeded 4 mmol/L. Updated research suggests that LT varies widely among individuals based on the testing protocol used and the length of the endurance event. For highly-trained athletes, LT might actually occur at a lower blood lactate concentration, as mitochondria are more efficient at processing lactate.

To add to the confusion nuance, exercise physiology studies sometimes divide lactate threshold into LT1 or lactate threshold 1 (blood lactate ~ 2 mmol/L) and LT2, when blood lactate exceeds 4 mmol/L, which I reflected in the above diagram. Even though a blood lactate concentration of 4mmol/L might not truly represent lactate threshold, it is the most common definition used in the literature.

Energy Sources

At Zone 2 intensity (blood lactate ≤ 2 mmol/L), mitochondria primarily oxidize fatty acids to generate energy.

As lactate accumulates and exceeds LT1 (> 2 mmol/L), there is increased oxidation of carbohydrates to generate energy, both aerobically and anaerobically.

With consistent training, the level of exertion at which LT1 is reached can gradually increase. In other words, mitochondria have increased their aerobic capacity, forestalling the need for anaerobic energy production.

One is therefore able to run faster or achieve a higher wattage while cycling and still maintain blood lactate below 2 mmol/L.

Mitochondria increase their aerobic capacity through three key mechanisms:

Increased biogenesis—the overall amount of mitochondria increases

Zone 5 intensity might drive this process more than Zone 2, although there is no firm consensus in the literature

Structural changes to the enzymes and expansion of surface area within mitochondria enhances their efficiency

Zone 2 intensity might drive this process more than Zone 5

Increased mitophagy—damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria are more quickly removed (and replaced through biogenesis)

Zone 2 intensity might again drive this process more than Zone 5

Approximating the Zones

Although analyzing blood lactate is possible in a non-clinical setting—similar to pricking a finger to test blood sugar—it is fairly unrealistic to expect anyone to perform such measurement on a regular basis.

We are thus forced to use non-invasive methods to approximate Zone 2 and Zone 5 blood lactate levels.

Talk Test

Zone 2: you can maintain a conversation without becoming breathless, although it is obvious you are exercising

Another marker of Zone 2 intensity is the ability to sing the alphabet and reach the letter G without taking an additional breath.

Zone 5: you can only say two or three words at a time without pausing for a breath

Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE): a subjective measure of intensity on a scale from 0 to 10, in which 0 is nothing at all, 2 is “light” exertion, and 10 is maximal exertion.

Zone 2: about 3 or 4 (moderate effort)

Zone 5 is above 6.5 (fairly intense effort)

Heart Rate Range:

Again, in this context Zone 2 and Zone 5 are not the same as conventional heart rate zones.

Following your heart rate during a workout will likely prove easier and more socially acceptable than talking to yourself. RPE can also be an especially crude tool and not always intuitive, although some may prefer RPE over monitoring heart rate.

Taken together, heart rate is likely to be the most actionable approximation of Zone 2 and Zone 5 lactate levels.

There are at least four major methods that attempt to calculate a heart rate range that roughly correspond to blood lactate levels in Zones 2 and 5. I have compiled these methods into this Google Sheet that can be copied to a personal Google Drive to aid with designing a training program.

For those interested, these calculation methods are explained in the Appendix.

Entering the Zones

Although one could potentially obtain the recommended dosage of cardiovascular exercise in a single session, spreading out exercise sessions throughout the week will likely be more feasible as well as more effective.

The Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) helps to determine who should seek advice from a healthcare provider before embarking on a new exercise program. If answering yes to any of the PAR-Q questions, consulting with a provider is best practice to understand specific limitations or modifications that may be required.

Please also note my disclaimer about medical advice.

Zone 2

Zone 2 training is somewhat more straightforward than Zone 5 protocols.

In a Zone 2 session, one aims to elevate their heart rate to the intended range and maintain that range throughout the session. This approach can be thought of as “steady state” cardio.

There is no set prescription for what type of cardiovascular exercise is best. Provided the movement can be performed safely and consistently (with regards to your current level of fitness, location, and access to equipment), it is a dealer’s choice. Walking at a brisk pace or along several graded hills, running, cycling, and rowing are all excellent options.

Rucking is increasingly gaining traction among individuals focused on longevity. Long practiced by the military, rucking is simply walking with additional weight carried on your back. Rucking can be an excellent way to obtain moderate, if not vigorous, exercise while performing an activity that is relatively safe (walking) and does not place undue strain on joints.

Although specialized (and expensive) “rucksacks” are available for purchase, one can get by with a standard backpack loaded with books or cans. Having good walking shoes with adequate support and traction is also an important consideration.

Zone 5

For Zone 5 training, it is most advantageous to utilize an approach broadly similar to HIIT.

I wrote about my favorite Norwegian 4×4 protocol in a previous post on VO2 max:

Begin each workout with a 5- to 10-minute warm-up at about 70% of your maximum heart rate.

Following the warm-up, perform four 4-minute intervals of work (hence, 4×4), aiming to get your heart rate to 85 – 95% of its calculated maximum (see below).

After each interval, actively recover (i.e., keep moving) at about 70% of your maximum heart rate for three minutes before progressing to the next interval.

You might need to briefly stop exercising entirely for your heart rate to decrease to 70% of its maximum during your rest periods. Your heart’s ability to quickly slow down during lower-intensity exercise should improve with training over time.

At the end of your fourth interval of work, proceed directly into a cool-down for 5 to 10 minutes, aiming to keep your heart rate under 70% of its maximum.

Again, you might find yourself briefly stopping all movement in order for your heart rate to recover adequately.

Not including the warm-up or cool-down, this session should take 25 minutes, as 4×4-minute intervals = 16 minutes and 3×3-minute rest periods = 9 minutes.

Maximum heart rate can be estimated using one of the following formulas:

MHR = 220 - (age)

MHR = 206.3 - (0.711 x age) (Londeree and Moeschberger formula)

MHR = 217 - (0.85 x age) (Miller formula)

An average of these three methods is used to calculate heart rate ranges in the aforementioned Google Sheet.

If you are planning to pair Zone 5 training with a Zone 2 session (i.e., a polarized training session), the warm-up portion could be omitted.

There are several ways to further modify the Norwegian protocol:

Increase your rest periods to be the same length as your intervals (each four minutes)

To shorten the overall session, reduce the intervals to 3 minutes and rest for 2 minutes in between each interval, or do one or two fewer intervals

I recommend that each high-intensity interval is at least three minutes and that the overall session lasts at least 15 minutes in length

To extend the session, you could add on additional four-minute intervals.

You might have realized that this 4×4 protocol does not ask you to maintain your heart rate in the putative “Zone 5” range for the entire workout.

Remember that with monitoring heart rate, we are merely trying to approximate the intensity of Zone 5 in lieu of directly measuring blood lactate. For that reason, there is no need to sustain your Zone 5 heart rate throughout the entirety of a Zone 5 session.

In terms of exercise choice, running, cycling, and rowing will likely lend themselves to Zone 5 training better than walking or rucking. If you choose walking, it will likely be necessary to find a steep hill or use a treadmill at a steep incline; if rucking, one might need to slowly jog and add increased weight for the duration of each interval.

In the span of a typical week, I recommend between two to five sessions of cardiovascular exercise. I usually devote Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday to cardio.

I personally allocate the remaining days of the week to resistance training and recovery, equally important components in our toolkit for a long, healthy life.

There are three potential approaches one could take to meet the above DHHS recommendations for moderate- and vigorous-intensity exercise:

Mix Zone 2 and Zone 5 training in the same week;

Solely train in Zone 2 during the week;

Solely train in Zone 5 during the week

If interested in approach (1), the aforementioned Google Sheet can also help determine the length of each Zone 2 and Zone 5 sessions based on your individual goals.

If pursuing approach (1) and you typically perform little to no cardiovascular exercise, you could start with the following program:

Three 15 to 30-minute sessions of Zone 2 training

One 15-minute Zone 5 session each week

This session can be tacked onto the end of a Zone 2 session, if more convenient. This is called polarized training.

Given the level of exertion involved in a Zone 5 session, it would be disadvantageous to schedule a Zone 5 session prior to a Zone 2 session.

If pursuing approach (1) and you are more experienced with cardiovascular exercise, you could start with the following program:

Appendix

The 3-Zone Paradigm

Mader et al. (1976) pioneered the simpler three-zone model for training intensity. Under this framework:

Zone 1 intensity refers to blood lactate concentrations ≤ 2 mmol/L

Zone 2: blood lactate between 2 - 4 mmol/L

Zone 3: blood lactate ≥ 4 mmol/L

In discussing Zones 2 and 5 below, I am again using the five-zone model examined elsewhere in this piece.

Zone 2

Four major methods for approximating the heart rate range of Zone 2 intensity are employed in the Google Sheet:

Norwegian method: 72 to 82% of maximal heart rate

Casado et al. (2021): 62 to 82% of maximal heart rate

Daniels (2014): 65 to 79% of maximal heart rate

The fourth method, pioneered by Joe Friel, places Zone 2 at 85 to 89% of lactate threshold heart rate (LTHR), which itself usually falls between 80 to 90% of maximal heart rate.

Zone 5

This is a much more simplistic calculation. Zone 5 intensity is generally considered to be met when heart rate is at 85% to 95% of its maximum.

Maximum Heart Rate

Maximum heart rate can again be estimated using one of the following formulas:

MHR = 220 - (age)

MHR = 206.3 - (0.711 x age) (Londeree and Moeschberger, 1982)

MHR = 217 - (0.85 x age) (Miller et al., 1993)

Here is a free calculator.